I study the protoplanetary disks of gas and dust that are surround newborn stars. Planets form in these disks, and their characteristics are crucial to understand the huge diversity of planets that we are just starting to discover. By studying these disks at different wavelengths and comparing observations with physical models, we can learn about their structure, evolution, and their connection with planetary formation. I also use interferometric observations to study these disks with very high resolution. You can find a summary of some of my research below.

My research interests include protoplanetary and debris disks, planet formation, and exoplanets. I am also interested in Bayesian statistics, data mining and applying machine learning to astronomy research.

Long-lived protoplanetary disks in multiple systems

|

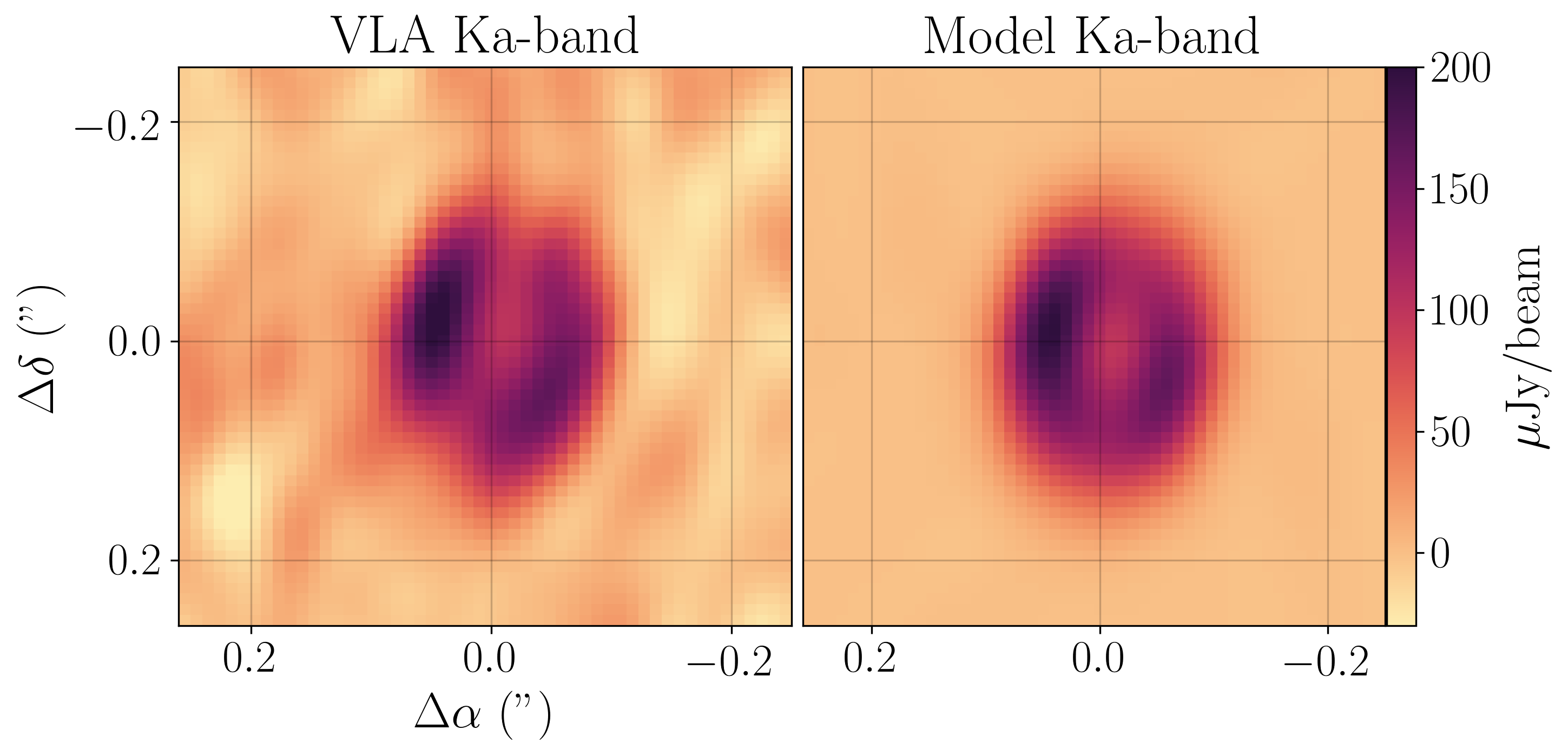

Many stars form in binary pairs or even in multiple systems (tree or four stars) and, in some cases, planets are also found around multiple stars. However, the effect of the companion(s) can be very disruptive and may disperse protoplanetary disks before any planets have formed. Surprisingly, there are also some examples of long-lived disks in multiple systems, and HD 98800 is a very good example of these: it contains four stars in two binary systems orbiting each other. Despite being 10 million years old (an age at which most single stars have dispersed their disk), the northern binary system still shows strong infrared excess from material surrounding it. In Ribas et al. 2018, we used observations of the Very Large Array to study this system in unprecedented detailed: we found the disk to be much smaller than originally thought (only 5 au in radius!), and resolved the gap in the disk carved by the binary system for the first time (about 3 au in size). We proposed that, in this case, the multiplicity of the system has locked the evolution of the disk, and it has been able to survive for longer than most disks around single stars.

The evolution of protoplanetary disks in the solar neighborhood

|

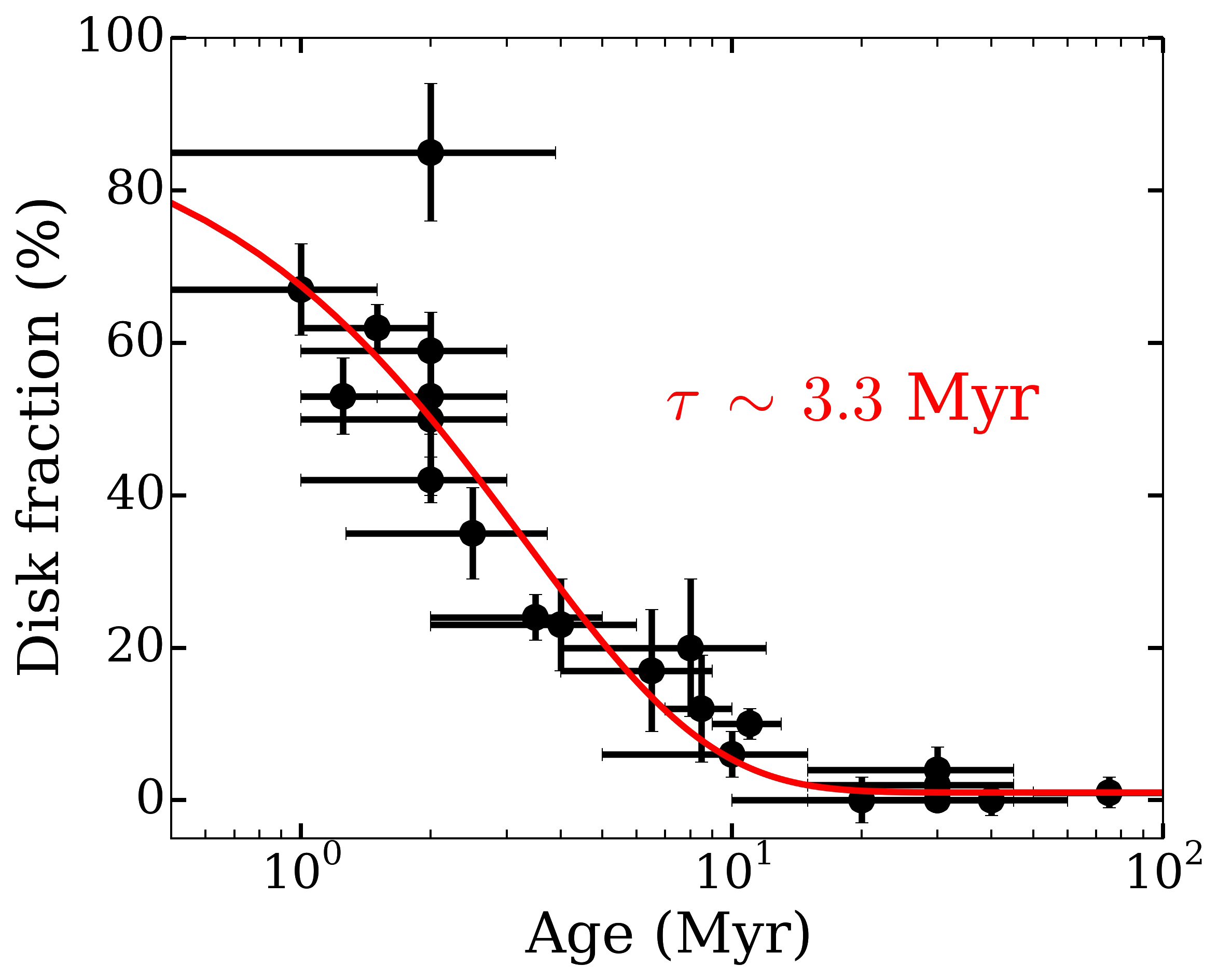

The evolution of protoplanetary disks determines the properties and fates of future planetary systems. However, these disks live for millions of years, and waiting that long is not practical. Instead, we look at different young star-forming regions with different ages. By looking at the fraction of disks as a function of age, we can infer how they evolve.

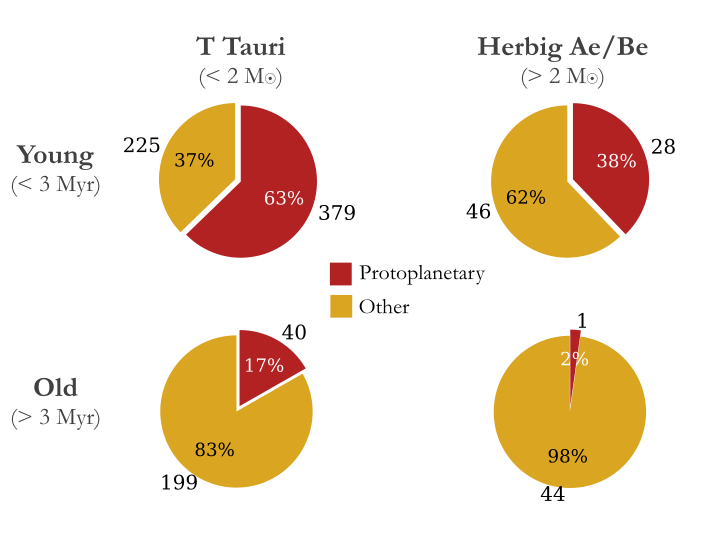

Disk evolution is usually studied by combining results from previous analysis, but samples compiled in this way are very heterogeneous, which can produce some biases. To overcome this issue, we compiled a large sample of young stars in 22 nearby star-forming regions and gathered data from different surveys and catalogs, covering from optical to mid-infrared wavelengths. After several homogenizing steps, we derived disk fractions for all these regions by searching for infrared excesses produced by disk around stars. We confirmed that protoplanetary disks disperse in less than 10 million years, and found evidence of the disk clearing occurring from inside out. These results were presented in Ribas et al. 2014. This sample also allowed us to study the importance of disk mass in disk evolution: the strong radiation fields and stellar winds around high-mass stars could disperse circumstellar disks faster than in the case of the low-mass stars. If this is the case, planets around high-mass and low-mass stars may have different properties. Using the large sample of young stars mentioned before, we found statistically evidence for a faster dispersal of protoplanetary disks around massive stars (Ribas et al. 2015).

|

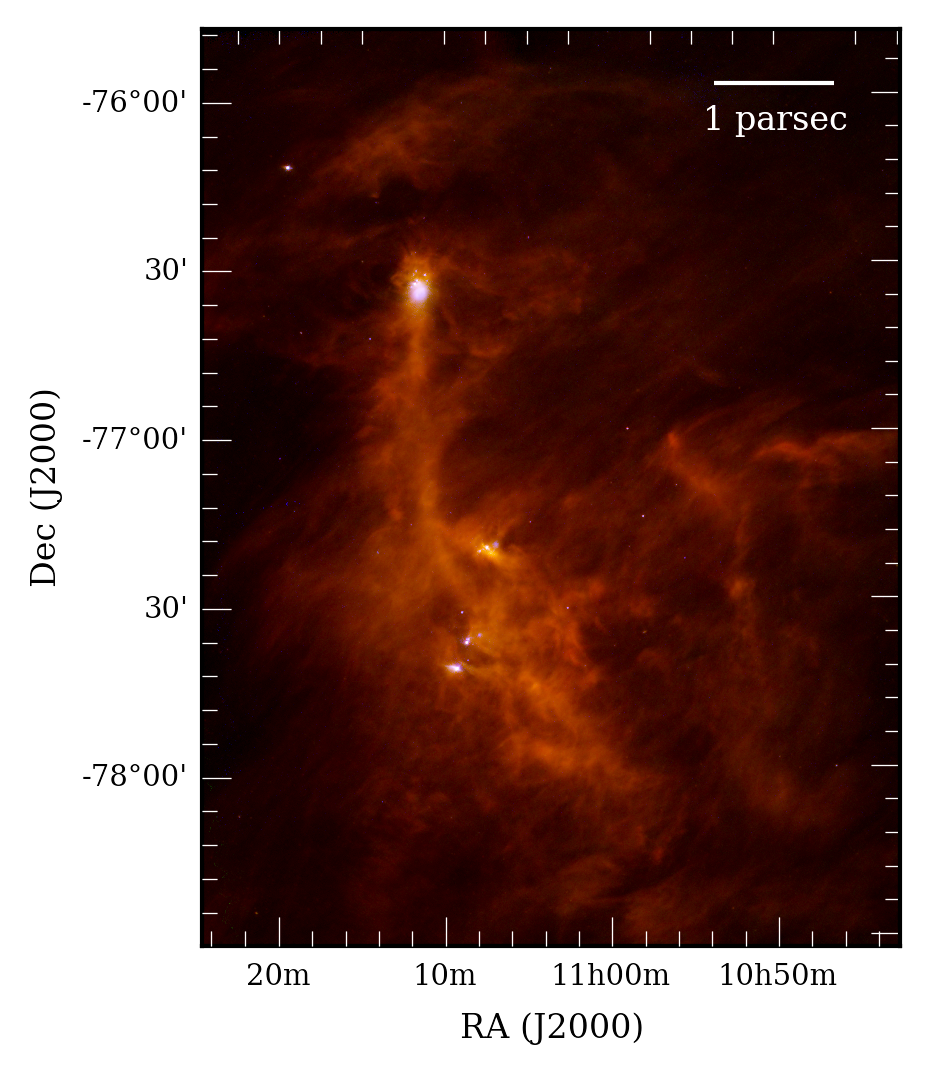

More recently, we expanded the wavelength coverage of our dataset up to millimeter wavelengths for three of the most studied star-forming regions in our sample: Taurus, Chamaeleon I, and Ophiuchus. Long wavelengths can be used to study the size and properties of dust particles in protoplanetary disks (the initial stages of planet formation), and we found that most sources in the sample showed some signatures of dust grain growth even at just 1 million years (Ribas et al. 2017). We are currently combining physical models of protoplanetary disks with machine learning techniques to analyze this sample, which will give us a unique look at some of their properties.

Herschel observations of transitional disks

|

Transitional disks are protoplanetary disks with gaps and cavities in them. They are extremely interesting because these gaps could be carved by newborn planets, and hence may be the perfect scenario to study in-situ planet formation or even detect planetary embryos.

Part of my research involved studying transitional disks with the Herschel Space Observatory. Herschel covered the far-infrared part of the spectrum and probed the emission from the cold, outer regions of disks. In Ribas et al. 2013, we analyzed Herschel observations of transitional disks in the Chamaeleon-I star-forming region and showed the potential of these data to identify transitional sources. We then investigated what these new data can tell us about transitional disks, by comparing these observations with disk models and statistics tools. We found that Herschel data can improve our knowledge of the structure and mass of these disks (Ribas et al. 2016).

Searching for warm debris disks around transiting planets systems

Debris disks are the remnant of planet formation, and can be found around older stars. They are similar to our Kuiper belt, consisting mainly of asteroids, planetesimals, and cold dust located far from their host star (several tens of astronomical units). Because they are cold, they emit in the far infrared regime. However, a small fraction of these disks are detected in the mid infrared, meaning that they are hotter (and hence closer to their star) than typical debris disks. These “warm” debris disks could be produced by collisions of bodies in the inner regions of the system. Even more interesting, these collisions could be the result of the dynamical excitation of an asteroid belt analog by planets in these systems.

In Ribas et al. 2012 we searched for warm debris disks around all the known stars with transiting planets, plus the planetary systems candidates from the Kepler mission. By including mid infrared data from the WISE survey, we identified 13 stars with promising mid infrared excess at 12 and/or 22 microns and compared the estimated location of the dust with the orbits of the planets/planetary candidates in these systems.